« Reviews

Bienal de las Fronteras (Biennial of the Frontiers)

Museum of Contemporary Art of Tamaulipas - Matamoros, Mexico

By Leslie Moody Castro

Matamoros, Mexico, is the most unlikely of places to travel to see and witness the shaping of an annual international exhibition of contemporary art. There are many layers to the complexity of the Bienal de las Fronteras, the inaugural biennial that took place in Matamoros in early March 2015, and an exhibition of this magnitude in this region certainly lays a foundation for a plethora of questions that must remain unanswered. The city of Matamoros is situated directly on the Texas/Mexico border in the northern Mexican state of Tamaulipas and is directly across the international bridge from Brownsville, Texas. The relationship between the border cities of Brownsville and Matamoros is one of divisiveness: You are either from “here” or “there,” U.S. or Mexico, and nothing in between. Add this to the recent spike in violence in the area and Matamoros has been almost completely forgotten, its citizens live in a constant state of fear, and it has the general feeling of a civil war zone.

It was beyond strange to travel to Matamoros to attend an international biennial at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Tamaulipas (MACT).

This is not by any means a region known for its contemporary art. The museum itself is a building designed and constructed by the famed Mexican architect Mario Paní in the late 1960s and was part of a major country-wide initiative to beautify the Mexican border between the 1960s and early 1970s to highlight the ever-increasing wealth in the region. This history, however, is a far cry from the current state of the project, much of which was left abandoned, but the MACT still stands as an example that the city of Matamoros once stood as a landmark across the border. Currently, Matamoros is witness to the slow state of decline it has undergone for the better part of the decade. Random street shootouts between local drug traffickers and Mexican police have become the norm, and the level of violence has become such a ubiquitous part of life that violence has become remarkably normalized.

Luz María Sánchez, V.F(i)n_1, 2014, sound sculpture, installation, 74 “shoot gun” audio players, 74 Micro-SD cards, 74 MP3 audio tracks , MDF white cubes 13.77 x 13.77 x 11.81 inches, variable dimensions. Installation view at Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Tamaulipas – ITCA – CONACULTA. Photo: Cecilia Hurtado. Courtesy of Bienal de las Fronteras (Biennial of the Frontiers), 2015

I arrived on the ground the day before the opening of the biennial. I was greeted at the airport by Enrique, a government employee at the museum, who graciously answered the many questions I had about the biennial and how it might be perceived by city residents. This was a huge initiative on its own, not to mention the fact that Matamoros has few if any resources to support artists, and the arts are not particularly valued in terms of culture or education. Hosting a biennial of international artists and gaining visibility on an international scale was beyond the scope of anything anyone had ever seen in that area.

Enrique was happy to talk about it, and as our conversation turned from the general logistics of hosting an international exhibition of this scale I began asking about his life in Matamoros, then turned back to the nature of the work in the exhibition in general. While the museum had received work from international artists in the past, this was radically different, and it was really obvious even before I had arrived. This was an exhibition that required site specificity, where many of the artists would be present and where the work wasn’t just being shipped from one place to another but required artists’ involvement in it.

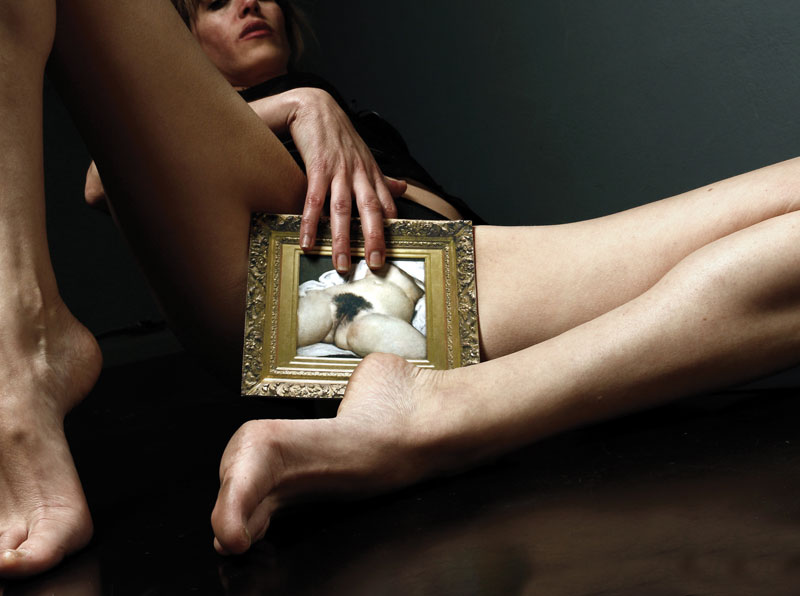

As my conversation with Enrique unfolded, we began to talk specifically of the work in the exhibition, and mainly that of first-prize winner Luz María Sánchez, whose contribution V.F9(i)n_1 (2014) is an installation of speakers that look exactly like plastic guns that play audio clips of sounds extracted from YouTube videos of shootouts from across the country. I asked Enrique if he believed the audience would take offense to the installation. A befuddled look came over his face, and he explained that “People are so used to guns, and the sounds of shootouts are so normal in the city, that it won’t actually be any different from daily life in Matamoros.” Enrique went on to explain that he was more concerned with a photograph by Verónica Meloni “that would probably shock the public much more.” When I pushed him to explain why, he went on to describe it as “a photograph with a woman’s legs wide open, and in between she was holding another image of another woman’s legs wide open.” He was blushing as he talked about it, and I moved the conversation in a different direction while making a mental note to look for the photograph, while also considering the irony that objects of violence would be better received than images that involve the naked human body.

My first stop after crossing the border was the museum itself. I had been there before, multiple times, in fact, but every other time the historical significance of the place had been completely lost on me. This time, however, I was witnessing the beginning of something that could shape culture in an area that so desperately needed it, and in the space that Mexico itself had created for culture more than 40 years prior. As I stepped into the Paní construction, the flurry of activity was obvious, and while the show was only mostly installed, the work was incredibly strong, and the design reflected the labyrinthine Paní aesthetic (at least in this building) quite seamlessly.

In an impressive showing for its inaugural year, the biennial boasted applications from artists and curators spanning 55 countries, whittling down its choices from the overwhelming 1,600 applicants to 55 artists who embraced the inaugural theme of “borders.” Partnerships such as those with El Museo del Barrio and the Guggenheim Museum strengthened the curatorial proposals and initiatives, and input from jurors such as Guillermo Santamarina of Mexico City’s Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, art historian and curator Julia P. Herzberg, and Emiliano Valdés, chief curator of the Museo Arte Moderno de Medellín, led the selection process.

I wondered how the theme of borders would translate in a space that was so clearly defined by so many borders, and mainly, how the chosen artists would articulate and translate the theme. The final exhibition was a maze of ideas, images and curatorial proposals that played with and problematized the definition of borders. First-prize winner Sánchez’s sound installation exposed the continued violence in Mexico, second-prize winner Maya Yadid’s video 443 follows a young couple driving a car along a desolate highway singing along at the top of their lungs to a song lamenting a better world. The work in the exhibition, and the exhibition in general, blurred borderlines and spoke of geographical borders, such as in that of Armando Miguélez Giambruno (USA), Emilio Chapela (Mexico) and Pinar Öğrenci (Turkey), of metaphysical borders, such as in the curatorial proposals of “Punto Ciego” and “Límites Nómadas,” and of borders in language, just to name a few examples.

While the exhibition in and of itself was a strong representation of work, the statement of organizing a biennial in this region is far more powerful than a traditional exhibition of contemporary art. I had the pleasure of having an informal conversation with the Biennial’s director, Othón Castañeda, during which I retold my story of Enrique’s comfort with seeing plastic guns in an exhibition but shock in response to the naked body. This prompted me to ask Castañeda why he had conceived of a biennial in Matamoros, and along the border region no less. It was obvious that his commitment to the show was far beyond a professional one, and he hoped that it would “open up the conversation about borders in order to show residents that they actually are not alone in this border conversation.”

Verónica Meloni, Collage, 2014, Digital photograph printed on Harman Crystal Luster 260 g. Epson Ultra Chrome K3, 59” x 43.3.” Courtesy of the artist and Bienal de las Fronteras (Biennial of the Frontiers), 2015

One of the most interesting things he recounted to me was that he had long wanted to start something similar in his hometown of Ciudad Victoria, but “Matamoros has the only institution that is dedicated and devoted to showing and exhibiting contemporary art. While the cultural implications and how the two cities go about those exhibitions and programs is obviously different, Matamoros was a natural site to host the project and creates a really important platform to shift the conversation about violence into one about the arts and education. With this biennial comes international attention for a good cause, not because another shooting has been reported in the media.”

Castañeda continued to elaborate, but more importantly explained his commitment to make the Bienal de las Fronteras a place of education, an initiative to open the dialogue between local and international artists and shift the common perception of violence to help develop a sense of pride within residents once again. The results remain to be seen, and if this is a project that takes root and sticks, the bigger impact will position the visual arts and culture as integral to the growth of the city as it attempts to rebuild itself post-drug wars. Hopefully, Matamoros will see the day when images of weapons are much more shocking than a nude body.

(March 5 - May 30, 2015)

Leslie Moody Castro is an independent curator and writer, living between Mexico City and Austin. She is a contributor to the online Texas visual arts journal Glasstire, as well as the Austin-based contemporary art e-journal, …might be good.

Filed Under: Reviews

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.