« Features

Clifton Childree - Miami’s Southern Gothic

By Claire Breukel

Having worked with Miami-based artist Clifton Childree on his sizable video and installation project Dream-Cum-Tru, I discovered that his artwork is a clear extension of his personality. As somewhat of an oxymoron, Childree is humble, kind and caring, yet carries a sense of humor that packs a punch! A punch that made him Miami New Times Best Artist for 2008. We could classify his comedy as toilet humor with the exception that it is a little dirtier and a lot more twisted, which gives his work a delicious edge.

This edge afforded Childree vast recognition beginning with the release of solo feature The Flew, a six-year long production which won him Best Feature at the Downstream Film Fest, Atlanta and at the Microcinefest, Baltimore and awarded him the South Florida Cultural Consortium Fellowship, an exhibition at the Miami Art Museum and finally it was named as one of the top 50 Midnight Movies made in the last decade by Cashiers Du Cinemart Magazine. More recognition came when She Sank on Shallow Bank and Something Awful, a vintage slapstick, was co-commissioned by the Miami Light Project and the Miami Performing Arts Center for the Here and Now Fest. It got better when Childree won the 2007 LegalArt Native Seeds grant and made It Gets Worse, which in turn won him the 2008 Locust Projects Hilger Artist Award, which made Dream-Cum-Tru. Childree told me he takes every opportunity to its fullest and sometimes exhausts himself …

CB - How did you first become interested in filmmaking?

CC - My mom had a collection of Super-8 films that she would play at my and my older sister’s birthdays. A few cartoons, [such as] Winnie the Pooh, but the last one would always be Return of Dracula, which was our favorite. My mom would giggle at how scared we all got and some kids would end up crying, and we were all only two to five years old! I was obsessed with this Dracula movie and thought it was real and would always ask my mom, “Has Dracula been here?” and “How far away is he?” Her answer was always, “Yes”, and “He’s gonna be here soon, we better get ready.” I enjoyed the feeling of being frightened, setting up the projector, closing the curtains and turning off the lights; it was a process to get it going, which made it all the more special. As I got a few years older, I became aware of filmmaking and created a notebook of all my special effects that I would use when I started making films. Super-8 was on its way out and hard to find, and video cameras were too expensive. But I managed to find some Super-8 film and produced my first film The Red Caped Killer with my lawn-mowing money.

CB - You now use a lot of 16mm film. What genres of filmmaking/ moviemaking do you draw on?

CC - I use a lot of 16mm film because I have a great 16mm camera that can film live action, single-frame animation, manual camera fades, and can rewind the film in the camera for double exposures. I am influenced by all the early silent films, but at the moment draw mostly on the early silent slapstick genre (Hal Roach, Mack Sennet, Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, Harry Langdon). If you want to melt away in a beautiful silent film, watch Murnau’s Sunrise.

CB - You have film as part of your childhood and you act in most of your films, sometimes playing both the protagonist and the victim. Are these roles somewhat autobiographical?

CC - Somewhat, but mostly it’s hard for me to get a friend over to play a role every night for several months as well as have their dick hanging out, so I end up playing most of the roles myself, but each film as a whole seems to represent a family member. She Sank on Shallow Bank is my grandmother; Something Awful is my grandfather, and It Gets Worse is my stepfather, which explains the belt-whooping sequence.

Filmmaking is largely time based. I don’t have money to pay people or the time it takes to get everyone together. I did a feature film years ago, which took months of preparation. On the night of the first shoot, one friend called me from Orlando and the other arrived and puked on the carpet he was so drunk.

I was obsessed to make this film and decided to do everything myself. I had a spring-driven camera so I could film myself, and although being in front of the camera can be limiting, when I’m on my own, I have more time to consider and it becomes like the process of making a painting. I used to connect a broomstick to the tripod, which I would bump to have the camera follow me but it was really rudimentary and bumpy [laughs].

CB - You choose to show your films as art films. What differentiates your work as ‘art’ films rather than any other form of moviemaking?

CC - I’m interested in exploring filmmaking. I’ve had my films accepted to a number of film festivals but I found that most films are designed to entertain, which means the narratives have to be clear. I’m more interested in pushing boundaries and experimenting, and this just fits in better in an art environment. Art people are more open to films being not what they are supposed to be.

CB - Your work later developed to include installation and even performance. Tell us a bit more about this development.

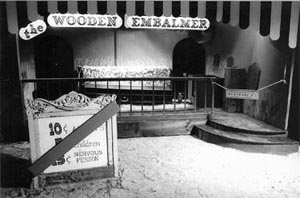

CC - The installations came about from having so much fun creating sets for my films. I would build sets and then after the films were made, tear them down. The set pieces in themselves were interesting. All the paintings and props from my early Super-8 films have been destroyed. I wasn’t an art school student, so at the time I didn’t see the value in keeping them.

CB - How did not going to art school affect your work?

CC - I had to figure it out and do my own thing. I wanted to go to film school and I started a course, but when I got there I found everyone too cool and laid back. I was so excited to be there and learn and was perhaps too intense at first, which scared everyone away. Instead I pulled out and used the money I had saved for the course to make a film. Growing up I went to a Catholic high school that had no art classes, so I never had that inspirational teacher. I remember being very inspired by my mom, with whom I would make these crazy paintings in the back yard.

CB - So your inspiration comes from your mom’s side of the family?

CC - My grandfather was in the navy. Ironically his name is Jeff Wall and he was bowlegged. Even as a kid I thought he was a character out of a slapstick comedy and he would tell the worst dirty jokes. I used to tell all my friends when he would be visiting, and he would walk in the door and we would all laugh. My grandmother was a vaudeville dancer and in the summer when the kids would visit, she would create art projects for us. In total there were about 15-20 kids including all our cousins and we would work on doing our own theatre shows. We would wear big baggy adult clothes and every night we practiced until the end of the summer when we did a grand performance. My mom would play the clarinet, Uncle Bubba on the washtub base, and Uncle Harry on the banjo. All the neighbors would come and watch the performance, so there must have been about 50 people in total. We would also sit around the table and tell ghost stories and my grandma had a glass eye that would pop out. It was all very southern gothic with a lot of dark humor and pranks. This was at Mobile Bay, Alabama where Mardi Gras started…it’s a very magical place.

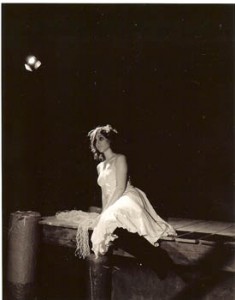

CB - You collaborate a lot with your fiancée Nikki who is a professional dancer and appears in most of your work. What is this like?

CC - She is a great actress, beautiful and has the perfect “cutesy-tootsy girl” look. It is difficult to collaborate with your partner, especially when I edit and insert scenes that make her look like she is ejaculating onto a hot dog! She doesn’t really like that too much.

CB - You also collaborate with musicians and select your soundtrack specifically. How does this work?

CC - My mom was a nun while she got her Masters in music and later quit to have kids. Her family was always quirky and naughty but would still go to church every Sunday. When she was a nun, she made reel-to-reel recordings of her recitals and I’ve used these in a lot of my films. I have friends who make music and compose soundtracks for my films as well. Sometimes I start with the music and the script often follows the sound. This is a logical way for me to create, as the ideas come from an intuitive place instead of a need to make sense. I’ve also used Thomas Edison’s wax ring recordings; this was the first way to record sound and these are available for public use online. There is a collection of turn-of-the-century recordings some as far back as the late 1800’s, which have gritty and textured sound that goes well with the films. Lately I’ve been using the work of local artist Rat Bastard who has a noise project called Laundry Room Squelchers. It’s a very intense sound and is perfect leading up to the end of the films when things get a little crazy. Most of the films start with a sweet slapstick and allude to a narrative. I like to draw the audience in with the idea of a possible fairytale, but then make it dark and twisted.

CB - You’ve just had a great film installation piece at the Pulse fair in New York. Anything dark and twisted coming up in the near future?

CC - What is important to me is the process of making work and showing it to people and what happens next has so far been unexpected opportunities. Upcoming projects include a group exhibition of Miami artists called Miami Noir at Invisible Exports gallery. I’m showing my film It Gets Worse, which features a broomstick that can show how many people are moving from Miami to New York. While I’m in New York, I will collect props for the installation component. I have a friend who is an urban explorer, so he will help me find washed-up flotsam and jetsam for the piece. I’m also doing a book as part of Gean Moreno’s [NAME] publication project. For this I’m arranging a group of 20 noise makers and will circulate the sound in an exquisite corps style, so each person makes a piece from the last sounds of the piece made before them. These noises will be included in a flipbook with photographs by Marcus Haugg- but we will have to wait for the noise to see what will be in the photographs.

CB - And any developments in your process?

CC - I can’t build sets in my backyard anymore, so I’m interested in building installations in public spaces, documenting them and leaving them there to interact with the environment. This is probably what the book will be about: structures made of junk and found objects integrating into run-down surroundings.

Claire Breukel: Curator and art critic. Since 2006, she has been the Director of Locust Projects, a renowned Miami-based non-profit specializing in alternative contemporary exhibitions.