« Reviews

Dak’Art: Off In Africa

Various venues - Dakar, Senegal

By Nevdon Jamgochian

Dak’Art, in Dakar Senegal, is the biggest, arguably the first, and the longest-running biennale in Africa. The 2018 exhibition that ran from May 3rd to June 2nd was a glorious mess. It featured a jumble of art worth seeing with some wonderful surprises but still, it was a sprawling, organic, and mostly undifferentiated heap.

The Biennale was so big that seeing even a double-digit percentage of the show was a serious accomplishment.

Halfway through the May to June exhibition, shows were still opening. Shows disappeared overnight without notice. Exhibitions decayed rapidly-being taken down and falling apart. Generally, video installations were not operational after the first week. Artworks were falling off of the walls, whole exhibits collapsed and were removed. The buildings themselves are in various states of repair: in non-hyperbolically condemned buildings to not yet fully built construction sites. The office that coordinated the Biennale was only a rumor as far as I was able to determine. The official guide was in short supply and the website incomplete. Information about Dak’Art’s 330 plus shows (most sites had multiple artists ranging from 75 in number to 4, so it had an uncountable number of artists in total) was passed along by rumor. Emails to the information office were not returned. I randomly ran into a press officer on the second day of the Biennale and was invited to a champagne party; I did not attend and she never responded to my later queries.

With fear of overgeneralization, the Dak’Art biennial is very much like my experience of living in West Africa. The center was the least interesting part and the unexpected and unheralded was the draw. Appreciation of chaos was necessary to really dig into the enormous spectacle.

The Biennale’s design itself is a mutt: it is half Venetian design with a juried show in seven locations and country pavilions (oddly Rwanda and Tunisia are the only two countries represented) and a Le Grand Prix for best in show. The other half of Dak’Art; titled “Off”-as opposed to the “In”- had dispersed shows not only in Dakar but also in regions all over Senegal. “In” was supposedly only for artists of African descent, except when it featured Asian and Latinx artists (at IFAN) and was held in official buildings. The non juried “Off” show was for anyone who had room to show art and featured art made by anyone at any time. There are more than 320 of these “Off” sites of wildly varying quality all over the city. As a sample, there was a show in the one shopping mall in the city, the preschool across the street from where I live, on Goree and Ngor islands, in basements, in the private residence of the Dutch ambassador and in abandoned houses. Adding to the impossibility of attending all of the sites due to time constraints, there were student riots for half of the month that closed down whole sections of Dakar. There was an official map but it did not show half the exhibits I went to.

The theme of the Biennale this year was the Red Hour. This is a reference to a line in Aimé Césaire’s play “And the dogs were silent.” The explanatory text, which I understood after it was parsed to me by someone who had been through the French school system and was able to explain the embedded references, refers to the dogs of colonialism and to the post-colonial African leaders who represent the continuance of colonialism. It went on to claim that the thesis of Dak’Art is that a multiplicitous and inclusive display of creativity is what offers hope and will destroy the post-colonial colonialisms of the current governments of Africa.

Fair enough; however, the “In” sites were state-sponsored and pointedly did not criticize the government of Senegal or address anything that might actually offend an oligarch (from what I saw, but again the exhibit was huge so I might have missed something). Environmental concerns were gingerly touched on-think of lots of stitched together wall hangings made of recycled materials. But there was nothing about unemployment, the abysmal gay rights, the prisons filled with the women who tried to have an abortion, overfishing by China, the rebellion in the south, encroaching Jihadists, abysmal healthcare or the dilapidated higher education facilities in Senegal.

When I first went to the “In” opening, it was filled with a different type of people than I usually see in the city in my circle. The sunglasses worn by the attendees looked like they were each worth more than my annual salary. The Red Hour had not arrived quite yet apparently.

The main “In” show at the old Palais de Justice, was uneven but the building itself is a wonder as an art site. It is actually condemned: cracks run down the middle of floors, ceilings are buckling, what looks like asbestos pour out of the walls. The organizers of Dak’Art made use of all of the old Supreme court’s rooms and antechambers to a stunning effect. Rooms were filled with dirt or mirrors or video installations, paintings and sculpture. All of which was VERY SERIOUS HIGH MINDED ART. Some of this was good: a room lined with images of North Africa pop artists from the 1970s and 80s by Amina Zoubar titled Muscicapidae playing the same music served to “…reestablish the reputation that Algeria lost in the civil war…” of a cosmopolitan hub. A wall text noted that many of the artists played and shown in the room had been killed during this recent conflict. The effect of listening to the light pop tunes and looking at the gaudy cassettes that seemed to be so optimistic about the future while thinking of how many of these artists were the victim of our conservative fundamentalist times was moving.

Temps Perdu II by Glenda León featured a very small hourglass perched on top of a 2.5-meter pile of sand in a large empty courtroom. The metaphor of lost time was in the tradition of bad art in that it was obvious-but in this case, this obviousness was an asset due to the scale and being in a municipal courtroom. Seething Red by Frances Goodman is a large (102 x 51 inches) assembled collection of thousands of acrylic press-on nails made into a lovely wall mount that looked shimmeringly alive. This piece’s take on beauty, desire and femininity were seductive and a little nauseating at the same time. This work seemed to be, in my visits, the most photographed piece. Peacocking through hair and clothes is a very big deal in this part of Africa.

Despite a few highlights in the Palais, most of the work was inscrutable, (wall texts were rare), many of the artists featured were big names, but one would not have known this from the shoddy and often inaccurate signage. There was a discernable lack of fun foregrounded. The Leopold-Sédar-Senghor Grand Prix award for the 13th Dakar Biennale was given to Laeïla Adjoviof for her Malaika series. This work featured somber photographs of a person growing wings. As the figure’s wings became more prominent, she shed her business clothes-in case you missed the point.

The “Off” sites were the meat of the Biennale. Aside from the Palais, all of the ‘In’ sites could safely be given a pass.

“Off” sites were a fun house. Even the many terrible shows gave the visitor the thrill of being in a space that one had not been in before: they were held in grand villas on the ocean, wrecked shells of buildings, parking garages, and along sewage canals. This time of year it never rains in Dakar and many of the installations were outside or in exposed areas, which was an effective way to display art. Among the dud “Off” sites (the bad ones usually looked like collections of art that did not sell in the 1990s- again, there was no filter for being an “Off” in this Biennale) there were a few are real stunners. In the ruins of the building called the old Malian Market, near the train station, a group of artists remodeled the caved in building and filled it with a massive homage to Dakar’s legendary artist Joe Oukam (Issa Samb), who passed in 2017. Oukam lived his life as art, more embodying the concept of art than being an object maker, although he did this too.

The Malian market faithfully reflected his aesthetic of artistic immersion. The old market was entered in a poorly marked doorway next to a row of street vendors. Once in the dark ruined market, one passed through a labyrinth of small dark rooms lit with colorful lights before entering a larger series of rooms that were better lit as the ceiling had collapsed. These rooms were filled with enormous sculptures, fabric hangings, suspended busts, a shrouded cow, planted trees in the floor, wall paintings, small installations depicting the traffic of Dakar, a life-sized dummy of Joe Oukam, a table of jars of rancid breast milk marked not for sale as well as red balls and string running the length of the rooms. These rooms led to a large courtyard with impressive tree trunk carvings, large metal clocks, a chained up outdoor library and a one and half meter nose placed in a tree.

This site seemed to best show the Dak’Art theme of creativity bursting as the path to the unfettered future. It was unexpected, joyous and light. Unfortunately, the Malian Market site had signs but I do not know who did what, or how it was funded. There was nothing I could find online about it either. As frustrating as the lack of information was, it was also lovely to be in such an egoless non-cash driven environment. Joe Oukam would have, by all accounts of people I talked to who knew him, appreciated the scale and absurdity of this place.

Other “Off” sites that were also worthy of note were The Grey (Matter) show put on in a half-built condominium on Beach Road. Unlike the Malian Market, this was a very finished exhibit, which featured four floors with nine artists. Like the Malian Market site, it was actually fun.

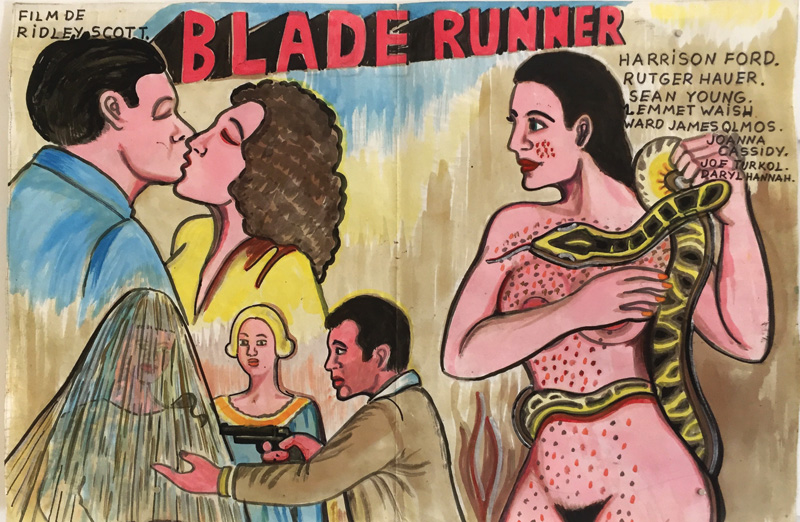

The work at The Grey ranged from the 83-year-old Ablaye Ndiaye Thiossane’s bizarre outsider paintings of his version of classic science fiction films to Senegalese album art paintings from the 1980s by Djibathen Sambou to the beautiful lesbian/ androgynous themed paintings by Benjamin Biayenda. Thiossane is best known as a musician and playwright but also has time somehow to make wonderful Francophone cardboard paintings of his favorite science fiction. His posters make the movies seem cartoonish, smaller and creepier than the actual ones. Sambou’s opening drew a large crowd of nodding grey headed hipsters; he is also a musician painter and has made all of his album’s art. The work was a refreshing take on psychedelia, with the palette reflecting more local colors of browns and reds and images: instead of long-haired beauties that one would see in the west in this type of art, we have minarets, baobab trees and eyes. Biayenda’s paintings seem to show some influence from Kerry James Marshall but are confidently half drawn and feature women in men’s clothes doing domestic chores. They are aesthetically very pleasing objects on their own. It cannot be overstated how homophobic this culture is, which makes the hanging of the work an act of bravery. Of course, gay women do not face the same levels of danger that gay men do here, but still the works seemed revolutionary in this context. I am excited to see how the 19-year-old (!) artist will evolve.

Next door, in an underground parking garage, there were collages made of old X-rays made by a Congolese group. The works were enjoyable but it was mostly entertaining to be in a strange yard with laundry hanging where cars normally parked, looking at art.

On the Corniche, the Luxembourgian Embassy sponsored a show at Galerie Atiss, a seaside villa, whose highlight was Emmanuel Tussore’s exquisite soap sculptures of ruined Syrian apartment blocks. The artist claims that soap was invented in this region and this is his inspiration, but I was impressed with how effective the fragile material of soap is when used to show the tattered city of Aleppo. Also successful were his large-scale prints of miniature soap sculptures. In these prints, Tussore made carvings of semi-destroyed historical ruins.

Dak’Art was a success. The thesis of the Red Hour is that creativity triumphs over the bureaucratic. This was proven by the overly curated In and the riot of imagination in the “Off.” Dak’Art is something that is worth putting on your calendar for 2020 and should be better known in the Anglophone West. To successfully attend the Biennale one should not see it as a thing to observe passively. This is not an event that one can enjoy without immersing oneself in it. This is easier and less intimidating than it sounds. Information is generously shared and events are easy to obtain access to. The traditional structures of the “In” events which are more beholden to western biennale models are perhaps a necessary gateway to the really exciting art of the “Off.” These organic and (to me anyway) more African-feeling events constitute a great new biennale model of the treasure hunt, which captures a real excitement of art’s possibilities.

(May 3 - June 2, 2018)

Nevdon Jamgochian is an educator, writer and artist who lives in Dakar, Senegal. He is working on a historical speculative fiction novel set in the 1920s Turkey where there was no radical separation of east and west caused by colonialism and genocide and the region continued as the leader of the arts world as it had been for thousands of years.

Filed Under: Reviews

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.