« Features

Jannis Kounellis: Non-Verbal Communication

Fresh from his solo exhibition at the Parasol Unit Foundation in London (on view until February 17th, 2012), Jannis Kounellis met with ARTPULSE to discuss his most recent projects and the most significant moments of his outstanding career, from the early days of Arte Povera to his relationship with painting and performance art, and why, after almost 50 years, communication is still the main driving force behind his work.

By Michele Robecchi

Michele Robecchi - You‘ve been very prolific over the course of your career. Have you ever encountered a difficult time with your work?

Jannis Kounellis - No, I don’t think so. In order to have a difficult time you need to have time in the first place, and I never had much. Maybe what can happen is to experience a temporary sense of loss. It’s a luxury that you can afford to have, but let’s be honest here-a manufactured crisis is not a real crisis. The truth is that from the very beginning you are aware that those moments of self-inflicted pain are acceptable precisely because you know how to handle them, whereby a real crisis is something you cannot beat. It has to happen sooner or later, it’s inevitable, and there’s no point in trying to anticipate it. But I don’t think it matters, big picture-wise. Life is a measurable quantity. There’s not much time after all.

M.R. - This is something that you realize in a determinate time of your life though. When you‘re young, you feel like you have all the time in the world.

J.K. - That’s true, but it didn’t quite work like that for me. Although I have spent 50 years or so in Italy, I wasn’t born there. I was born in Greece. I moved to Italy when I was 18. It was a big change, and it gave me a different perspective on what time is about from very early on.

M.R. - So you don‘t think that at this stage of your professional path, after so many exhibitions and with a wide range of signature materials immediately identifiable with your art, there‘s the risk to succumb to expectations by replacing creativity with experience, as if you would pick up ideas from a hypotethical repertoire?

J.K. - No, it doesn’t even cross my mind. I think exclusively in terms of linguistic possibilities. Yes, the risk of being academic is always there, but if you’re capable to stay emotionally involved with what you do, you’re safe. I never felt restricted by what people would call ‘style.’ Pier Paolo Pasolini once declared to have found his own language in the 1950s and how that discovery set the cornerstone for everything he has done afterwards. Having your own language is not a position. It’s not an overnight invention. It’s a grace. Historical circumstances generated a particular situation, and that situation naturally evolved into what I’m doing now. When we started, we deliberately decided to trespass the limits dictated by the canvas to explore the visual and cultural situation around us. We didn’t want to be entrapped in some kind of mannerism. Freedom is about resisting style, not embracing it. New forms need to be defined by a concept. The reason why we moved out of the canvas was to establish a more direct relationship with the space and the viewer. It was a natural process, almost a question of two poles attracting each other. This is not to say that I hate paintings, because I don’t. But artists locked in their studio all the time clearly don’t enjoy the same level of interaction with the public that we do.

M.R. - I‘ve noticed that you switched from singular to plural halfway through your answer. When you say ‘we,‘ do you mean you and the other artists associated with Arte Povera?

J.K. - No, Arte Povera was more about participation. The idea of blurring the borders between the work and the space around came much earlier on. It goes back to the 1950s, to the post-war days, when there was a desire to experiment with different media and establish a more direct dialogue with the audience.

M.R. - When you abandoned the canvas, one of the first language options you explored was performance…

J.K. - I never considered them performances. The living horses I exhibited in Rome in 1969, for example, were in the L’Attico Gallery for 15 days. They were arranged along the walls, close to the foundation of the building. I wasn’t trying to be sensational, I was only interested in mapping the space, in creating an image that would stand for change.

M.R. - It‘s interesting that you associate the concept of performance with provocation.

J.K. - I olnly mention it because that’s what a lot of people thought I was trying to do at the time-being provocative, whereas I was only interested in defining the space.

M.R. - How about other works, like the violinist on the rooftop of the gallery you made a couple of years later?

J.K. - It was based on similar premises, although in that case it was more a theatrical issue. Drama is a strong element in Italian culture. Look at Caravaggio’s paintings. You can’t rule these elements out if you decide to work within a specific tradition. What we were doing was very different from Minimalism, for example, which at the time was at its peak. Minimalist artists were our counterparts in a way, but our work wasn’t so dogmatic. I think we were a bit more open and modern.

M.R. - Have you ever been tempted to work again with living images, as in those cases?

J.K. - You know, the thing is, everything is alive. What’s ultimately important is the interaction you establish between the viewer and the object. A sculpture has the same potential, the same energy of a fiddler playing on a roof or a horse in a gallery. It doesn’t matter if it’s a living thing or not. Sometimes it works, other times it doesn’t, but at the end of the day it’s still the same game. Jackson Pollock is a good example of how you can live through your vision regardless of physical restrictions. A painter like Giorgio Morandi had an urge to control the canvas, whereas Pollock wanted to walk away from it.

M.R. - How about Lucio Fontana‘s cuts? Wouldn‘t you say he was trying to break away from a conventional way to intend painting as well?

J.K. - Fontana’s cuts are very conspicuous. They manage to be an integral part of the canvas while breaking its integrity at the same time. They are a laceration. In a way they resemble the wound of Christ in Caravaggio’s The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1601-2). The big difference is that in Fontana’s case, what we are dealing with is not an image, but a direct relationship with the canvas.

M.R. - You still consider yourself a painter.

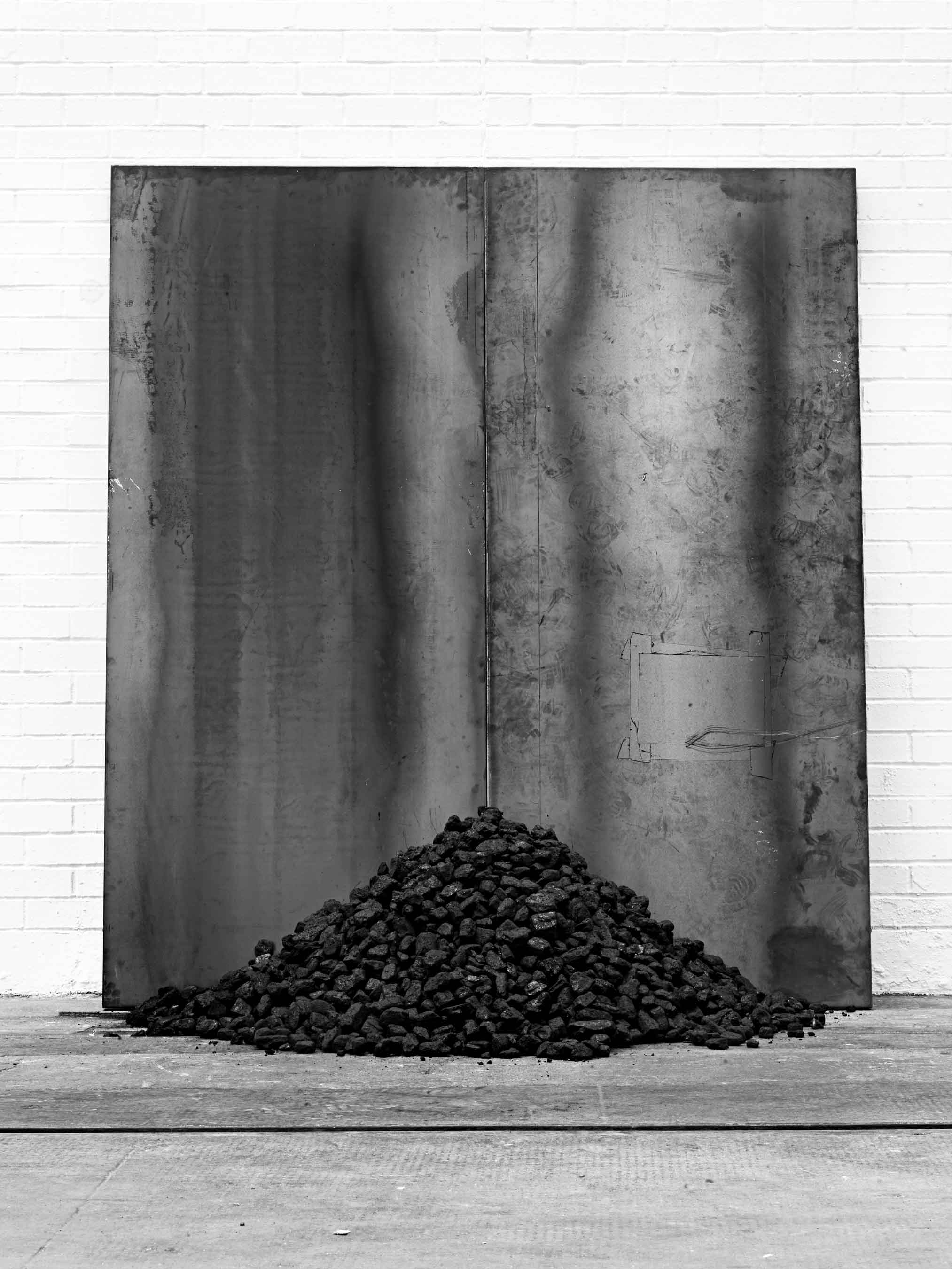

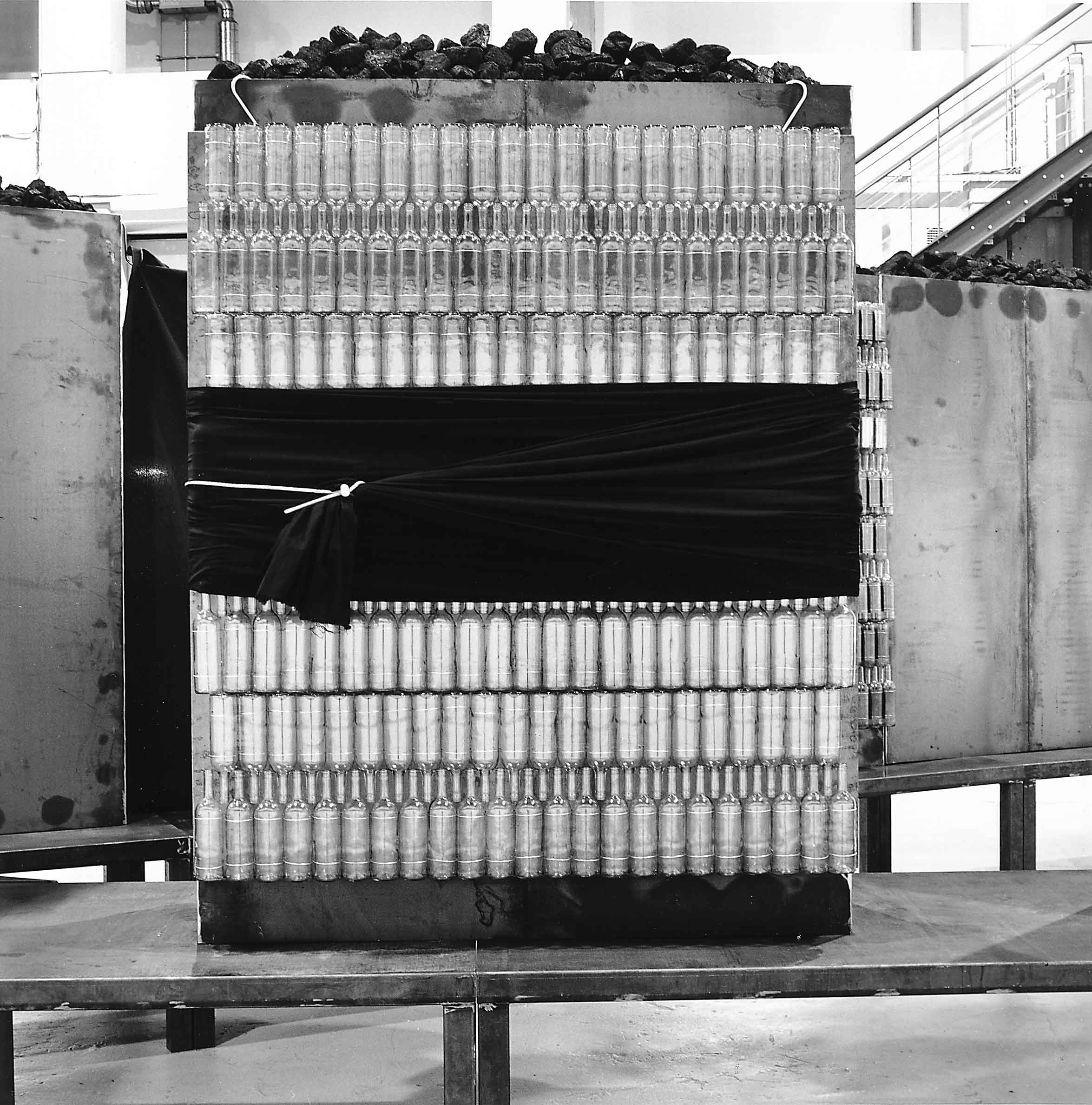

J.K. - I do, because my work is about images. I never denied being a painter, even when I stopped making painting in the 1960s. I don’t physically paint anymore, but I work using the same principles. Of course, works like the one I made at Ambika P3 in London are different, but the essence of painting is still present. The centerpiece in London was a sculpture shaped as a ‘K.’ There were black textiles, which emphasized the tragic element of the installation, and white, green and brown bottles. They looked like church windows, if you think about it. It was like a Gothic cathedral.

M.R. - What about charcoal? I‘m asking because it‘s a material that has a very strong social and historical meaning in the U.K.

J.K. - That’s something I started using a long time ago, in 1967. It’s a recurring theme in my work. For me, it’s more about Victor Hugo and the Charcoal Burners revolutionary movement. You’re right, it’s a socially characterized material. It stands for energy, progress and fatigue, but the geological problem is not so important for me. Charcoal is something I learned about through 18th-century literature. It’s not about a form or a media. A parrot or a piece of charcoal are the same thing. It’s like being a novelist. This is just the grammar I use to create an image.

M.R. - The letter ‘K‘ in London was intended to form a labyrinth-another recurring theme in your work.

J.K. - My interest in the labyrinth goes back to an exhibition I did at Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome in 2002. It helped me focus on 40 years of work. It was almost like a ghostly presence I finally managed to pin down. I made other labyrinths at Fondazione Pomodoro in Milan (Atto Unico, 2007) and at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin (2007). The one in Berlin presented an opposite dynamic to the gallery. The space is mainly composed of windows. It’s a beautiful space because the city is always present, but also very difficult. You need a strong work to counterbalance it, to create a contrast. In London, it was in an underground space that sort of looked like a labyrinth already. The ‘K’ wasn’t standing up. It was a dead letter. It was laid on the ground, like an epitaph. It resembled a dead Christ. I have many memories associated with the letter ‘K,’ but it doesn’t hold a particularly literal or personal meaning for me. It’s the tenth letter of the Greek alphabet. It doesn’t practically exist in the Italian one. I’ve been to China recently. Their alphabet is made of ideograms. They almost look like impressionist landscapes.

M.R. - What were your impressions of China?

J.K. - Contemporary art as we know it is still relatively new over there. There is a very distinct mentality, but it’s possible to find common ground. I’m obsessed with dialogue. I’m happy to show my work everywhere I go, but I need a reference point. The difference is that the responsibility to establish a contact between the artist and the viewer is essentially down to the artist, whereby with other artists it’s a mutual experience. I met many artists familiar with my work. They’re eager to see what you do and show you what they do. It’s a very important exchange.

M.R. - Do you think this desire to communicate can be pinpointed as one of the ultimate reasons that keeps you going?

J.K. - Absolutely. It’s the reason why I started making art in the first place, and it kept me going to these days. It’s not just limited to communication though, it’s about expression too. Communication operates on different levels, but when it comes to art, it’s an issue that can be satisfactorily resolved only within a spatial dimension.

Michele Robecchi is a writer and curator based in London. A former managing editor of Flash Art (2001-2004) and senior editor at Contemporary Magazine (2005-2007), he is currently a visiting lecturer at Christie’s Education and an editor at Phaidon Press, where he has edited monographs about Marina Abramović, Francis Alÿs, Jorge Pardo, Stephen Shore and Ai Weiwei.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.