« Reviews

Morten Viskum / In retrospect

Sørlandets Kunstmuseum - Norway

By Mari Sundet

In February, the Norwegian artist Morten Viskum (1965) opened his first retrospective exhibition at Sørlandets Kunstmuseum in Norway. An extensive catalogue was also published in conjunction with the exhibition, and these two forms of documentation serve the complementary purpose of cataloguing and categorizing an oeuvre that has, over the last fifteen years, only been overshadowed by the extensive debate the works have evoked. Morten Viskum’s art has been accused of being sensational, ‘popular’ in the most negative sense of the word (as antithetic to an idea of art as a form of transcendental knowledge, too pleasing to the ego of the ‘layman’ and therefore too connected to the whim of common taste, triggered only by the use of common denominators that make up the platform unifying man in life: birth, death, vanity, and the transitory character of existence) and for being in bed with the ‘capitalists’ of the art market, that still constitutes a red blinking lamp in the face of Norwegian art society (that, as information to the reader, is subsidized through and through by the social democratic government). The nature of the debate and the angles of the discussions (accusations) chosen say, of course, nothing of the quality of the work, whether it be positively or negatively charged. The quality of any artwork is, in any case, not the focus of this text. The question is rather what these debates tell us, what kind of values they speak of, and what it is that has such an ability to evoke anger in the audience (especially within the arts itself)?

Confronted by Morten Viskum’s art, paintings and installations subsumed in the uncanny presence of organic residue, the spectator is not only confronted with a sensational artwork, but also, and unwillingly, the parameters of one’s own existence. For the keen ‘reader’ of art, the mere mentioning of this (cause and) effect is superfluous, a given, and beyond all, a well-established cliché within the parameters of art. The more important question then, when faced with Viskum’s work, is whether, within the compounds of art (as catharsis), the work can be read as anything more than a reproduction of traditional tableaus, used and reused to keep works of art within the compounds of the public (as of the people) sphere.

Can art that communicates themes of life and death, in an overtly existential (traditional) language, based on very traditional themes, make a stand today? Are these statements of contemporary expressionism only a reaction against a (dry) conceptual tradition that has successfully managed to infiltrate all levels of artistic life, whether as a conscious strategy to keep itself in tune with the remnants of an Anglo-American neo-avant-garde or, as an involuntary gesture, signaling its place within a critical tradition, with traces back to Enlightenment ideas, however ‘silent’ this knowledge might be at the present time? My references to a ‘traditional, artistic language’ might surprise the reader of this text, especially if one has seen one or more of Viskum’s works. He emerged on the Norwegian art scene in the mid-nineties, with an installation named Rotte/oliven Prosjektet (Rat/olive Project) (1995), where he substituted olives in regular convenient store jars with rat fetuses and placed the jars in twenty stores in the five biggest cities in Norway. The response was overwhelming, but, of course, not surprising. For the Norwegian audience the project touched various issues, mainly circling around what boundaries can be crossed over, in and by art, and whether that which has set out to describe life in all its virtues also has the right to mock its sanctity.

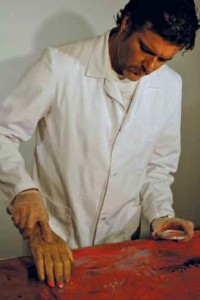

The rat/olive project is well-documented in the exhibition at Sørlandets Kunstmuseum. Tracing through a chronology of works, this installation kicks off a tour within Viskum’s artistic world, reaching a culmination in two separate projects, different in methods, all the while circulating around overlapping and integrated themes. The first of these is The Hand that Never Stops Painting (1997), initially a performance where Viskum painted with the severed hand of a dead body. Over the last decade this one hand has multiplied into three, where The Black Hand is the last in the series. The same response was granted to this project as the rat fetuses in olive jars, and even more so since it was now the flesh of a human being that was being desecrated. It did not help the situation that the artist refused to explain where the hand came from (it might have been better if it was clear that the hand was donated to the artist, just as any one of us could donate our body to science) and that, even in a secular country such as Norway, the integrity of the human body was threatened. The fear of damaging the integrity of the body is still, secularisation aside, connected to an idea of the human soul (and the loss of it), and in this sense the discussions around the project took an extremely traditional (again existential) and ancient turn. Isn’t the whole ‘concept’ of art to conjure a strategy to avoid facing one’s own mortality? (A situation where the artist and the spectator represents two sides to the same story.) And wouldn’t a hand that never stops painting be the ultimate mockery of the finality of life itself? I would claim that if this were the bottom line of the project, it would be an endgame - a final surrender to art as therapy for the lost souls in a world without the comfort of God, priest, or even a psychologist. Contrary to this I would claim that the project is based in a more (art) internal sphere, where the hand in itself represents a slap on the cheek of the self-absorbed and self-righteous claim of artists who see themselves as deliverers of exactly the service that the “lost” souls of a God-less world crave after.

The same reference can be made in discussing the next project I wish to mention, the Monogram series. The Monogram series can be described as a pun based on Robert Rauschenberg’s Monogram (1955), where the neo-Dadaist mix of high and low culture constituted an early expression of Pop art in the making. The Pop artists wanted to break down the barriers between exactly this idea of high and low in culture, by fusing the visual elements of the everyday with the refined and established forms of fine art. Fifty years later it is clear that this effort to break down the castle walls segregating the common man from his more cultured peers has failed and that Pop no longer necessarily has any ties with its namesake, that of popular. Seeing a documentary about Rauschenberg’s Monogram at the Museum of Modern Art in Stockholm, the audience flocking around the goat with the wheel tucked around its belly, also made me realize that in making a new construct based on seemingly diverging elements, what Rauschenberg actually did was mould a golden calf out of the ashes of the old. And just the same, the result was a new idol (icon) for worship and adoration. Viskum’s Monogram series mocks the pretention that art can take on the role of the divine and plays out the iconography of the neo-avant-garde on a stage originally built to deconstruct the high walls and mansions of fine art, just to build new ones, maybe even more impenetrable.

This brings us back to the beginning. Can works of art, both infused with references to traditional iconography, not necessarily in appearance, but definitely in spirit (it is easy to find parallels to the shock and awe in the reception of Viskum’s art in every generation within canonized art history and it can seem like the whole concept of art history, and especially the strategy of the avant-garde, is driven forward by the testing of boundaries between humans and their treasured values), as well as the neo avant-gardes dismantling of the mere concept of iconography as such, tell us a little bit about both? And more important, can they tell us something about the need for and function of art, not only in the face of a basic human want for representation, but more acutely, in the face of art’s (artists and art professionals) pretention of supplying the world with answers to problems, initially formulated by themselves. The answer is a positive maybe, and in this arena Morten Viskum’s art represents a negation within the sphere of relational aesthetics, keeping the audience at a distance while orchestrating that which actually defines our lives. In these works the avant-garde focus on the psychology of the individual is reduced (maybe also elevated) to the realm of discourse, not necessarily to that of the popular, but definitely, and defiantly, to that of the social.

(February 13 - May 2, 2010)

Mari Sundet, an art historian, is currently assistant manager at Vestfossen Kunstlaboratorium in Norway.

All images © Morten Viskum. Courtesy of the artist and Son Espace Gallery (Barcelona)

Filed Under: Reviews