« Features

Painting Pros and Cons. A Conversation between Laurie Fendrich and Peter Plagens

Peter Plagens is a painter who also writes art criticism for The Wall Street Journal and other publications. Laurie Fendrich is a painter and professor of fine arts at Hofstra University who writes frequently about art and other matters for The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Peter Plagens - I’m interested in the disjunction between the public and private aspects of painting. On the one hand, its public presence in what I’d call the serious art world is pretty diminished. Oh sure, there are an awful lot of painters out there, a bunch of painting shows in the New York galleries every month, though not nearly the percentage of even 10 years ago, and still a huge art-school and college-art-department cohort of painting teachers. But painting is pretty much overwhelmed by various artists’ ‘projects’ involving installation, video and performance. On the other hand, the worst painters I’ve ever known (no names, please) were the ones who were totally hipped on personal expression, who thought any consciousness of history, rules, breaking rules, ‘issues,’ etc. was totally irrelevant. Almost nobody cares any more about ‘issues’ within painting-e.g., how minimal can it get? What makes it become sculpture? Are ’signature’ brush strokes a corruption?

Laurie Fendrich - Painters would actually do themselves a big favor if they’d stop fretting over painting’s relevance, or whether painting can regain its status as a major player in today’s art world. Once the photograph was born, it was in the cards that painting would eventually become an anachronistic art form. The invention of film, followed after that by the invention of digital images, sealed its fate. The surprise isn’t that painting is diminished in stature, but that it remains as lively and alluring as it does-and to an awful lot of very educated, urbane, smart and sensitive people. That said, it’s nostalgic to dwell on ways to make painting regain its powerful cultural position. It can’t do that-at least any time soon. Instead, we should be asking: In the face of the massive cultural shift away from painting, what is it about painting that continues to attract smart artists and smart viewers? And while we’re at it, because it’s gotten super tough out there, we might also ask what would help up-and-coming, talented painters make their way as painters in the contemporary art world.

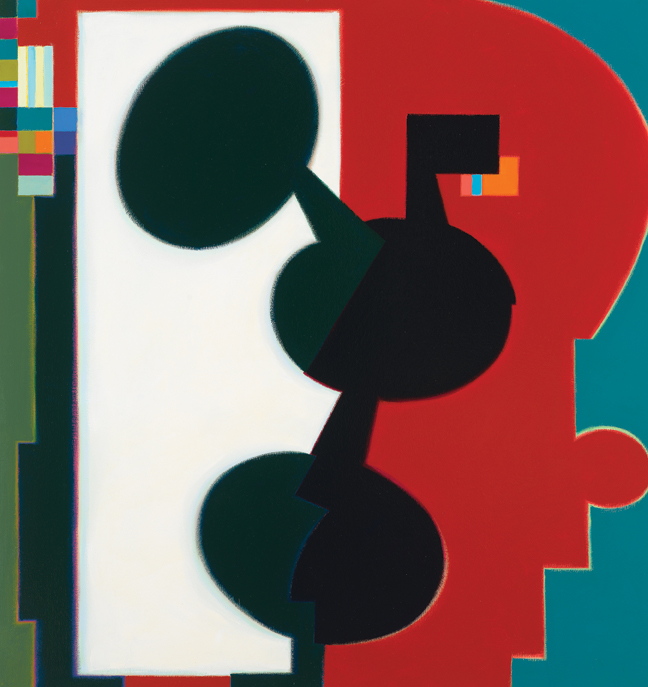

Peter Plagens, I Don’t Give a Damn / Every Moment Counts, 2010, mixed media on canvas, 48” x 38”. Nancy Hoffman Gallery, New York.

P.P. - Part of this is because painting has become pretty much a niche medium in the big-time contemporary art world. When’s the last time a painter-painter represented the U.S. at the Venice Biennale, stole the show at the Whitney Biennial, won one of those big art prizes like the Hugo Boss, or was the subject of art-world buzz in the same way that, oh, say, Sarah Sze or El Anatsui has been lately? What’s left is the old appeal to history: attaching oneself (on one’s own say-so, of course) to the glorious tradition of Giotto, van der Weyden, Velázquez, Manet, de Kooning and-to keep this from being entirely a boys’ club-the likes of Joan Mitchell, Alice Neel and Agnes Martin.

The argument that painting has value because of its history, in the way a lot of current painters invoke it, is merely valuing habit on a cultural scale. “There’s been a lot of painting for 600 years, so why not keep it going?” This seems weak to me. The only reason I can see to be a painter these days is precisely the existential pointlessness of it, plus the fact that it sometimes looks pretty nifty on the walls.

L.F. - Until the last century, it was commonly assumed that painting was the highest art form, but in the 20th century, we gave up hierarchical ranking of the art forms. Even so, most painters, even though they recognize painting is now a minor player in the art world, remain quietly convinced that painting remains the ‘queen of the arts.’ And they’re on to something with this. Even if painting in general has been shoved off to the side, and even if most paintings are bad or mediocre, painting possesses a staying power unlike that of any other art form. Because painting is motionless in an age where we see everything continuously changing, in a metaphorical sense, it reminds us of permanence. It fools us into seeming as if it were a permanent object. You can linger over it and return to it over and over again. What its critics see as its debility-that it’s a rectangle hanging on a wall-makes you recognize it instantly as art, and indeed it’s next to impossible to see a painted rectangle hanging on a wall and not consider it to be a work of art.

But even though you’re right that valuing painting’s history boils down to no more than celebrating habit writ large, serious painters look for painters from the past in order to lift stuff. As Picasso famously put it, “Good artists borrow; great artists steal.” Artists who embrace the historical roots to their paintings are not embarrassed; on the contrary, they like this part of painting.

One reason artists continue to make paintings is simply that it’s fun to make them. It’s fun to push goopy, colored pigments around a flat white rectangle until you arrive at an invented picture. It’s deeply satisfying to build a painting from the ground up, and to see the trace bits of evidence of all the steps it took to get to that final picture. On the other hand, herding cats is a breeze compared to controlling paint and color, and the act of painting is as frustrating as it is fun. In a way, painting is nothing but a series of mistakes, each one a correction of the previous one. You don’t get this in a photograph, an installation or a computer-generated image.

Unfortunately, a lot of art teachers destroy the joyful part of painting by forcing their students to think about their paintings in all the wrong ways. The hipper ones want their students to think about abstract theories (most of them borrowed from literary theory and philosophy). Buying Harold Bloom’s “anxiety of influence” whole hog, as if it were absolute truth, many art teachers bludgeon their students with the hubristic notion that “everything’s been done” in painting and originality is impossible. The prevalence of this truly arrogant outlook demonstrates how easy it is to fall victim to the dominant ideology of an age, and it doesn’t begin to acknowledge that our ability to predict the future is limited. Artists are always changing history as well as changing in history. Originality requires a degree of forgetfulness and illusion. Today’s young painters need to find a way to move past self-consciousness-a crippling thing for an artist-and get on with painting. Great paintings and painters are at our backs, yes, but they should inspire us, not intimidate us. Anyway, painters aren’t stupid. They know painting is out of sync with the dominant art forms of our age. So what? We go against our age. We paint because painting remains the sole art form able to express human yearning for material objects to transcend their physicality.

P.P. - The late abstract painter Paul Brach once said that one day painting will be viewed as cloisonné is today-a visually seductive but culturally irrelevant medium. Yes, painting keeps on keeping on, but fewer and fewer of the artists who seem to have any cultural clout are painters. And unless the electric power grid totally flames out and the Internet goes the way of the dirigible, that trend is going to continue.

I’ve used the similes of the Spanish Empire and jazz in describing the situation of painting today. The Spanish Empire doesn’t rule as much of the world as it used to, but Spain has a great language, literature and culture; there’s certainly nothing to be ashamed of in being a citizen of Spain. And while jazz no longer tops the charts, as it did with Louis Armstrong in the 1920s, it’s still a deep, complex, lively and ever-evolving art form that has its own dedicated-if numerically diminished-audience. There’s nothing to be ashamed of in being a jazz musician or jazz fan. It’s just that being a Spanish jazz pianist isn’t going get you the audience or the ink that English-language pop stars get today.

As for my own paintings-which, like any paintings, can be read with psychological accuracy by a sufficiently versed, intelligent and perceptive person-I worry that they’ll reveal me to be stupid, clumsy, uninventive, cowardly, lazy and tasteless. Maybe that risk in painting, though, is one of its virtues, and that an artist’s shortcomings are much more easily covered up in installations, video and pretentious text art.

L.F. - I couldn’t agree more about your last comment. A painter’s shortcomings are in your face, whereas artists who make other forms of art-especially installation artists-almost always make art that looks as if it must have an important idea behind it. Early in modern art, writing manifestos-and coming up with ‘isms’ in art-helped artists advance their cause, but people would laugh at any group of artists that tried this today. All artists now work under the enormous umbrella of pluralism, where everyone is bound, at least outwardly, to ‘respect,’ or at least tolerate, all forms of art, including-albeit somewhat patronizingly-painting. How can you have a passionate ‘ism’ or write a manifesto, at the same time you promote tolerance of everything?

If there’s one thing painters could do to help give painting more gravitas, if not an actual edge over other art forms, it would be to refuse to show their art in exhibitions with anything other than other paintings; heck, still sculptural objects would be OK. But anything that makes noise, moves, is generated by a computer or machine, or expands beyond the confines of the rectangle should have its own exhibitions. Why? Because showing all kinds of art in a single exhibition flattens everything. More important, while other art forms gain aesthetic credibility from being exhibited alongside paintings (a painting hanging near a pile of detritus helps the pile of detritus look as if it belongs in a gallery), painting is inevitably dragged down and made to look conservative and even fuddy-duddy whenever it’s exhibited near art that isn’t painting.

P.P. - An old piece of vaudeville performer’s wisdom was never to work with children or dogs. Talented or not, they always stole the show just by being onstage. Same thing, I suppose, with painting versus noisy installations and performances. But media and styles do poop out, especially after the basic positions have been manifested and the in-between slots occupied. Picture the styles of abstract painting as points on a compass, with, say, Ad Reinhardt at north, Jackson Pollock at south, Piet Mondrian at east and a Willem de Kooning 1970s abstraction at west. Fill in the NNE, WSW, etc., directions with whomever you choose, and then the points in between them the same way. The point is that you can, just off the top, without consulting a book or the Internet. Other than a painting fetishist, who can possibly be interested in, or excited by, some painter who comes along and positions him/herself in between the painters already occupying 92 degrees, eight minutes and 17 seconds?

L.F. - Your compass analogy is compelling. Given the pizazz of so much installation, computer-based and video-based art, I’m tempted to agree. But then I remember that all of contemporary art is a mere sideshow to contemporary culture, which mostly consists of pop music and movies. Painting is not the only art form having to fight off enervation. Even at venues like the Venice Biennale, which I’ve seen on multiple occasions over the years, once you’ve wandered through four or five rooms of boundary-less art, or art that operates ‘in the gap,’ or art that stems from some sociological or genetic ‘research,’ ennui easily sets in. How many rooms full of stacked chairs or dank mushrooms, or dangling colored strings hanging from the ceilings, or piles of pigment rising from the floor, or white rabbits hopping about, can you take before you feel you’ve seen it all and start longing for a Paul Klee?

A better analogy than your compass is to look at the way painting resembles a game, where play is possible only if one abides by certain rules. The rules of painting aren’t written in stone, obviously, but they include such things as staying within the bounds of the rectangle and its flat surface, pushing colored pigments around with some specifically designed painting tools, exploring color depth and relativity, and producing a unique work of art that is supposed to hang on a wall. While all this strikes non-painters as anachronistic, quaint, arbitrary and limiting, the rules are what make painting so durable. Actually, without the rules, it’s physically and philosophically impossible to paint a painting.

P.P. - The interior, or structural virtues of painting as I see them-and these are not necessarily original thoughts-are A) the strength of its having several and powerful conventions (sculpture since about 1960 has had absolutely no conventions, and it’s in a precarious position because anything can be a ’sculpture’); B) the fact that it stands still in a frantically moving world-the only other pictures you can contemplate are photographs, which, with digitalization, have completely lost any necessary claim to being non-fiction, and photoshopped photographs are airless paintings with uninteresting-and to me almost repellent-surfaces, or drawings and prints-the best of which are what painters and sculptors do on the side; C) the fact that, with many paintings (de Kooning’s Excavation does it for me) you can stand and view it from just about the same place as the painter painted it-there’s a visceral connection-something you can’t say about photography, video or film; and D) the medium itself, it’s like drawing with flesh-the person who invented the brush is to art what the person who invented the wheel is to civilization itself.

Abstraction has a subtle advantage in painting today. It’s not competing with the deluge of reproduced figurative images that started with the invention of photography in the early-ish 19th century, continued through film and then video, and has now exploded with digital technology and the Internet. Abstraction lets paint be paint and not try to substitute it for cloth, skin, foliage or armor. Of course, people-including art sophisticates-are more attracted to ‘pictures of something rather than pictures of nothing,’ but I’ll take an audience that is minority-savvy and discerning enough to get greater pleasure out of ‘pictures of nothing.’

L.F. - Most people make too many demands on painting. Painting emerged out of both the sacred and the profane and has a natural affinity with decoration and adornment. Yes, it can be profound, and painters certainly want their own paintings to be more than decoration. But to glean delight and meaning from a painting doesn’t mean that all paintings, to be good or even great, must deliver the profound, deep meaning of Velázquez’s Las Meninas. Making a painting that’s arresting in an intriguing way is hard enough. To paint requires talent, patience and perseverance, and to appreciate it requires standing still and looking hard-not exactly hallmarks of our democratic age.

A short list of some of the contemporary painters Laurie Fendrich and Peter Plagens admire:

Ron Linden

Katy Crowe

Denise Gale

Terry Winters

Mary Heilmann

Andy Spence

Gary Stephan

Louise Fishman

Marie Thiebault

James Biederman

Judith Geichman

Mark Mullin

Howard Buchwald

Heidi Pollard

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.