« Features

The Dematerialization of Art: Notes from the Artifact’s Era

In spite of the growing push toward dematerialization of works of art since the pronouncement of the death of art at the end of the nineteenth century, the path toward the immaterial has been historically inhibited by the still dominant notion that it silences art, and that in one way or another translates it into an emphatic artifact forced to repeat the demands of circulation and consumption of an obsolete artistic system, still governed by modern practices.

By Janet Batet

In 1960, Yves Klein made public a photographic montage in which he crosses into the void. The poetic work summarized some of the most radical tendencies of Post-War Art: the predominance of concept over form, validation of documentation as an artistic act in and of itself, the influence of the process over the artifact, simulation, the quest for the immaterial, among others. Seen from a distance, the work becomes a transgressive act and an emblem of the pursuit of decisive liberation from the quasi-sacred white cube.

Claire Fontaine, Passe-Partout (Paris 10ème) http://www.lysator.liu.se/mit-guide/mit-guide.html / http://www.hackerethic.org / http://www.lockpicks.com / http://www.lockpicking101.com / http://www.gregmiller.net/locks/makelockpicks.html, 2004, Hacksaw blades, bicycle spokes, mini-mag lite, key-rings, metro-tickets and paper-clip. Courtesy the artist and Chantal Crousel, Paris. Private collection, Paris. Photo: Claire Fontaine.

There have been many ups and downs in this process of liberation, which is still underway. Without a doubt, one of the pitched battles has been the redemption of the creative act of the artifact. The artifact as a unique and physical piece -object of desire- makes the artistic system possible through three of its fundamental facets: documentation, collection and the art market. In the midst of this process, the dematerialization of the work of art presupposes new challenges.

THE ULTRA-CONCEPTUAL ART: MAPPING THE IMMATERIAL

Although the term dematerialization of art tends to be associated with the advent of Net art around the nineteen nineties, advances in the search for immateriality imply a progressive process that begins with the historical Avant-garde1 and reaches its climax with conceptualism.

Coined in 1968 by Lucy Lippard and John Chandler, the term dematerialization is associated with what they call “ultra-conceptual art,” which “emphasizes the thinking process almost exclusively” and “may result in the object becoming wholly obsolete.”2

The change in the notion of authorship and in the concept of the work of art is made evident in two seminal texts of the decade: Opera Aperta, (Umberto Eco, 1962) and La mort de l’auteur, (Roland Barthes, 1968). To these fundamental precepts are added the work of artists like Sol Lewitt, Lawrence Weiner and The Art & Language group, among others, who would revolutionize the notion of the work of art, affecting sensitive areas of creation like authorship, originality, intertextuality, etc. that become fundamental areas of interest of so-called digital or immaterial art.

For Sol Lewitt “The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.”3 The artist’s work process is based on strict instructions -like “data”- that predetermine the existence of the piece. The instructions that are the basis of LeWitt’s creations are “programming codes” that consider the “random” as a creative element.

Lawrence Weiner, for his part, proposes the constant adaptation of the statement to variable spatial and physical conditions, conceiving art as a group of relationships more than a closed piece: the artwork has value insofar as a cultural relationship in its capacity to adapt. Weiner’s creative process represents a fundamental contribution to digital art in general and specifically to that aspect of Net art that seeks the transgression of immaterial existence through realization in the physical space of the gallery.

Lastly, The Art & Language group4 would contribute the meta-textual analysis associated with a work of art and a strict questioning of so-called modern and mainstream art. For immaterial art, questioning the role of an artist as a creator of a particular type of material object would be crucial.

BINARY THINKING: THE IMMATERIAL ART

It is precisely in the midst of this change in aesthetic paradigm represented by “ultra-conceptual art” that conditions are forged for the birth of new media art.

Two essential distinctions are imposed on the classification and differentiation of digital or immaterial art. The first -introduced by Alan Kay- is dynamic media vs. static media. Dynamic media, or hypermedia, implies a dynamic reading as opposed to traditional media like painting, photography, television or cinema, which are characterized by a unidirectional, predetermined and unambiguous reading.

Once this differentiation is established, dynamic media can in turn be subdivided into two categories: tool or medium. In the first instance, the artist uses the computer as a tool in the creative process but the output is separate from the computer and the software. In this sense the work becomes an artifact, its logic of distribution and collection responds like that of traditional artwork.

In the second case, however, the computer and the software become the medium on which the creative act is experienced -and in many cases managed. In this last subgroup, art becomes immaterial and ephemeral. It only exists during each public-works encounter, each of these encounters being unrepeatable and part of a chain of interactions that energize and enrich the work of art.

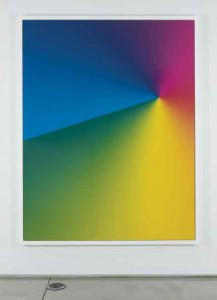

Cory Arcangel, Photoshop CS: 84 by 66 inches, 300 DPI, RGB, square pixels, default gradient "Spectrum", mousedown y=8900 x=15,600, mouse up y=13,800 x=0, 2009, unique c-print, 84” x 66” inches. Courtesy of the artist and Team Gallery, New York.

In contrast to other procedural manifestations in which duration is fundamental but whose temporal existence is predetermined -as is the case with performance- immaterial art imposes new challenges. Traditional documentation becomes ineffective, since recollection and preservation of the work requires the safeguarding of codes that generate it, the technical framework -or support- on which it was conceived, as well as a collection of external links that continually energize the work. An emblematic example is Jackpot, 1997, by Maciej Wisniewski, acquired by the Walker Art Center in 1998. Playing with the structure of the slot machine, the work randomly loads different URL’s contained in its database. As many of these addresses disappear, the game becomes inoperable.

This vital goal of preservation has been assumed by various institutions that seek alternatives means for the recording, systemization and curatorship of digital art, specifically Web-based art. They include The American Museum of the Moving Image, Walker Art Center’s Gallery 9, SFMOMA’s e-space, the Variable Media Initiative, the Whitney Museum of American Art’s artport, The Tate Britain, among others.

Other concepts that demand immediate reevaluation are those of authorship, originality and copyright. In this sense one of the most burning legal issues is the one revolving around the so-called remix5 culture. This growing phenomenon, whose arrival is related to the emergence of Web 2.0 culture, presupposes an open creative act through which the user -previously passive- becomes the creator. In the era of the digital culture -where the dynamic media proposed by Kay dominate- the once unidirectional and emphatic discourse -imposed by analog technology or static media- is subjected to a process of critical rewriting. It is what Lawrence Lessig presents as a vital epochal change when he coins the terms read-only culture (RO) vs. read/write culture (RW) or remix culture.

Lessig, Director of the Edmond J. Safra Foundation Center for Ethics at Harvard University and Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, is one of the founders of Creative Commons. A fervent activist of the remix culture, Lessig has waged a crucial battle to relax the use of copyright, which often criminalizes the creative act reducing it to “piracy.” Lessig proposes the coexistence of two parallel economies: the commercial and sharing economies -a dual model better adapted to the hybrid nature of contemporary society in which traditional or static media and dynamic or digital media coexist.

CONTEMPORARY ART: TRACKING THE IMMATERIAL FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF THE OBJECT

In the system of art, one of the most typical features of contemporary hybridization is curiously rematerialization. Digital work seeks a means of existence in the tangible world through a kind of “instance” that endows it with corporeality.

However, the system of art -as well as the legal apparatus that governs our culture- still responds to a traditional model of economic realization where the mechanisms of exhibition, distribution and conservation are constrained by notions such as commercial value and uniqueness that impose a return to the artifact. The works of art described below represent an examination from an artistic standpoint of this problem of transition characteristic of contemporary culture.

The oeuvre of Cory Arcangel flirts with the limits between digital culture and traditional culture. His series Photoshop displays large-format prints resulting from the use of gradients with the aid of paint bucket. The descriptive title of the piece contains the “data” necessary for the realization and printing of same, the piece becoming a play on words that scoffs at its own existence “in situ.” Nevertheless, Arcangel refers to these pieces as unique and when he thinks of them, he considers them painting because of their referential dialogue with the history of painting. The work that is immaterial in principle, now printed on photographic paper and exhibited as original, implies a reworking of traditional notions of the art object and those inherited from the tendencies of the dematerialization of art in which “data,” ready-made and “Do-it-yourself” are fundamental.

His Drei Klavierstücke op.11, is an expression of the read/write culture phenomenon stated by Lessig. Starting with amateur videos posted on the Internet, Arcangel recreates Schoenberg’s Opus 11. Drei Klavierstücke op.11 is an exercise in reappropriation in which the artists begins with the score of the opera and hundreds of cats on pianos downloaded from the Internet. The resulting piece far from being an act of “piracy” is the embodiment of remix culture.

The notion of collective and anonymous creation is incorporated by the French collective Claire Fontaine. Passe-Partout (Paris 10eme), addresses the problem of dematerialization from one of its fundamental angles: copyright and market relationships surrounding a work of art.

Passe-Partout (Paris 10eme) is a key ring with the keys to the Parisian gallery that markets the works of Claire Fontaine. The keys, made with a technology employed by the FBI, in which the material utilized is so malleable that they may only be used once, allows the holder access to all of the collective’s major works but at the expense of the legal implications resulting from the act and the destruction of the oeuvre Passe-Partout.

In Trust (2010), Claire Fontaine presents art gallery blank checks. The framed check replaces the work of art, thus reducing the creative process to its monetary expression.

In the UK, The Museum of Ordure’s work starts with an act of destruction. A symbol of traditional museums, which in an attempt at conservation adulterate the purity of the very artifacts that are their raison d’être, The Museum of Ordure undertakes the logical destructive process implied by the passage of time as an active part of its collection, which is immaterial in its entirety.

The work of Félix González-Torres portrays a very noteworthy approximation of the act of dematerialization of a work of art. For González-Torres the full realization of the work is only possible in the act of transference, as evidenced in Untitled (Portrait of Dad), 1991. The work composed of an endless supply of white mint candies must maintain an ideal weight of 175 pounds (the body weight of the artist’s father) and it is precisely this cycle of constant flow -consumption and renovation- that endows the piece with spirit. The disintegration of the work is in fact the basis of a regenerative act. Each piece of candy becomes a kind of host that conquers the physical limits of existence, becoming a propitious channel for the transmigration of the soul.

Temporary Services, a Chicago art collective comprised of Brett Bloom, Salem Collo-Julin and Marc Fischer, builds precisely on González Torres’ notion of the dissolution of the work of art insofar as being a unique original. One of the group’s pieces consists of a Guide to Re-Creating “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers) by Félix González-Torres. The effective piece fuels its transcendence by transmitting the central idea to a vast public.

THE RE-MATERIALIZATION OF ART: AN ECONOMIC TASK

Contemporary society is relentlessly advancing toward a service society where e-economy is based on a strong speculative sense that shapes our daily lives and the direction of contemporary economic activity is characterized by a sense of “paid-for-experience.” In midst of this change in paradigm, the notion of the artifact continues to figure as an imperative governing and guaranteeing the realization of an art market still based on modernist precepts.

The dizzying parody initiated by Klein in 1960 appears to suspend itself in time, meeting up with the also symbolic leap of Ray Johnson, “the most famous unknown artist in New York,” and founder of the New York Correspondence School, who in 1995 decides to plunge into the void from eastern Long Island’s Sag Harbor bridge. For those who knew Johnson well, the act was a deliberate gesture that closed the cycle of his public interventions that, in contrast to established happenings, the artist curiously called “nothings.” Today that action is still an open wound.

NOTES

1. Specifically with Dadaism and its positioning, through anti-art, against the traditional standards of art and Marcel Duchamp with his ready-mades, and later Fluxus, mail art and figures like John Cage and Allan Karpow.

2. “The Dematerialization of Art.” John Chandler and Lucy Lippard. 1968. This essay is followed by the essential anthology Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972. Lucy R. Lippard. New York: Praeger,1973.

3. “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art”. Sol Lewitt. Artforum. June, 1967. <http://sol-lewitt.livejournal.com/1263.html>

4. The group founded in 1967 in the United Kingdom by Terry Atkinson, David Bainbridge, Michael Baldwin and Harold Hurrell. The group was soon internationalized in New York and Canada, later incorporating figures like Joseph Kosuth, Charles Harrison and Mel Ramsden, among others.

5. Lawrence Lessig. Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy. Penguin Press, 2008. Available as a free download at Creative Commons

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Alberro, Alexander. Stimson, Blake. Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology. The MIT Press, 1999

- Cox, Geoff. Krysa, Joasia. On immaterial curating: the generation and corruption of the digital object.

<www.anti-thesis.net/contents/texts/curating.pdf>

- Dietz, Steve. NeMe: Collecting New Media Art: Just Like Anything Else, Only Different. <http://www.neme.org/524/collecting-new-media-art>

- Lippard, Lucy. Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972. New York: Praeger,1973.

- Joasia Krysa (Editor). Curating Immateriality. Autonomedia (DATA browser 03), 2006. 288

- Paul, Christiane. Context and Archive: Presenting and preserving Net-based Art.

<http://143.50.30.21/static/publication09/np_paul_09.pdf>

- Rifkin, Jeremy. The Age of Access. The New Culture of Hypercapitalism Where All of Life is a Paid-For-Experience. Paperback, 2001.

- Berry Slater, Josephine. Unassignable Leakage: A Crisis of Measure and Judgement Immaterial (Art) Production. <http://www.kurator.org/media/uploads/publications/DB03/BerrySlater2.pdf>