« Reviews

The Disappeared

Sara Maneiro (Venezuela, 1965), Los insepultos (The Unburied), 1993, 2 blueprints, each 37” x 384”. Courtesy of the artist and University of Texas at El Paso.

The University of Texas at El Paso

June 18 - September 11, 2009

By Raisa Clavijo

Over the summer, the University of Texas in El Paso presented “The Disappeared,” an exhibition organized and curated by Laurel Reuter, Director of the North Dakota Museum of Art, which has traveled to various institutions in the United States and Latin America. In El Paso, “The Disappeared” was displayed at The Stanlee and Gerald Rubin Center for the Visual Arts, The Centennial Museum and the Union Gallery. The show assembled a large number of Latin American artists, whose works reflect the extreme violence unleashed by various military dictatorships that governed that region in the second half of the twentieth century. As a consequence, numerous citizens were made to disappear in countries, such as, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Guatemala, Uruguay and Venezuela.

The show included works by: Nicolás Guagnini, Marcelo Brodsky, Fernando Traverso, Antonio Frasconi, Sara Maneiro, Iván Navarro, Arturo Duclos, Nelson Leirner, Cildo Meireles, Luis Camnitzer, Ana Triscornia, Luis González Palma, Juan Manuel Echavarría and Oscar Muñoz. Also presented was the project Identidad, developed by a collective of thirteen Argentinean artists in an effort to assist the Abuelas de la Plaza de Mayo, whose sons, daughters and grandchildren disappeared in that country during the last military dictatorship.

The original idea for this exhibition arose from various articles by Lawrence Weschler, contributor to The New Yorker, published between 1987 and 1989 1. Weschler’s writings revealed to the American public the reality regarding “the disappeared” in Latin America. These texts were the spark that caused Laurel Reuter to begin a journey through the history of Latin America, only to discover that several visual artists were creating eloquent and robust works based on this theme. Little by little, an exhibition project took shape that would make known the work of these creators and would contribute to denouncing these atrocities to the rest of the world.

Most of the artists assembled in “The Disappeared” placed in the visual, the weight of their strategies covering denouncement and the salvaging of memories. A majority of them employ the language of photography and video installation to present us with impressive testimonies. In agreement with Nelly Richard, we can affirm that photography fulfills a decisive function in reflection based on memory from a critical and social standpoint (2000:165). While traces of “the disappeared” are erased with the passage of time, their images, caught in photographs and family videos have created their own temporality, and constitute the only resource available to gain access to the past. At the same time, these become a recurring means of highlighting the uncertainty and the vacuum left by the missing.

For their part, other creators have delved into the conceptual, finding precise codes with which to subliminally spread their messages of protest, at times taking advantage of the symbolism of objects and materials to evade censorship.

There is not enough space in this short review to analyze each of the 26 works that comprise the exhibition. Below, we randomly select some examples that convey an idea of the magnitude of this show.

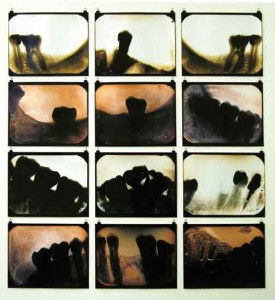

One of the most startling works is Mueca de Berenice (Berenice’s Grimace) (1995), by the Venezuelan, Sara Maneiro (1965). It belongs to the series Los insepultos (The Unburied), through which the artist addresses the repression that her country suffered during the “Caracazo” in 1989, which resulted in more than 300 deaths. When, years later, mass graves were uncovered, Maneiro took photographs of the remains and created this series of photographic plates of the set of teeth of one of the anonymous corpses. In Latin America, a lack of resources prevents many remains from undergoing exhaustive forensic examination. Her work demonstrates how, over time, vestiges of the bodies of “the disappeared” turn to dust, are lost and become one with the earth.

For his part, Fernando Traverso (Rosario, Argentina, 1951) takes up the theme of the city and the traumatic events that marred its landscape. For Traverso, who was part of the resistance against the military dictatorship, abandoned bicycles are the symbol of “the disappeared.” The artist created an installation with 29 silk flags, each of which displays the ghostly image of a bicycle in memory of his comrades. The silhouette of the bicycle constitutes a metaphor for absence. The artist also intervened in his native city. Working without being seen, with spray paint he traced the silhouette of 350 bicycles leaning against various buildings in different sections of Rosario, one for each of the citizens who disappeared throughout those years. In this city, where the urban scars of state-sponsored terrorism were still fresh; Traverso undertook to make them even more visible.

Proyecto para un Monumento (2005) by the Colombian, Oscar Muñoz (1951) questions the relationship between the portrait and memory, grief, death. In his country, violent deaths are so commonplace that people no longer choose to protest. The works of Muñoz offer a message that can be applied to the entire exhibition: the dead only live on in remembrance and in the spirit of the living. This oeuvre presents a series of synchronized videos in which the artist draws the face of the “disappeared” over and over again on a stone and it continually disappears, just as the facial features of the dead are gradually erased from memory.

The presentation of “The Disappeared” took on special meaning in the social context of El Paso. Innumerable immigrants cross the border each day seeking refuge in the United States, fleeing from the violence assailing their countries. Furthermore, the brutality experienced daily in Juárez, which neighbors El Paso, is not so different from that which is being denounced in the exhibition.

The show included a wide spectrum of activities, such as: parallel exhibitions and movie showings at various locations around El Paso and Juárez including: UTEP’s Union Cinema, Trinity First Film Salon, El Paso Museum of Art, Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez (UACJ) and People’s Gallery at El Paso’s City Hall.

“The Disappeared” causes us to come face to face with the thousands of tragedies that have still not found justice. It breaks the traumatic and abetting silence of oblivion. Through their work, the artists combat amnesia in order to prevent these atrocities from recurring.

NOTES

1 Articles published by Lawrence Weschler were compiled in the book, A Miracle, A Universe: Settling Accounts with Torturers. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

WORK CITED

Richard, Nelly. “Imagen-recuerdo y borraduras.” Políticas y estéticas de la memoria . Santiago de Chile: Cuarto Propio, 2000:165.

Raisa Clavijo: Art critic and curator. BA in Art History (Universidad de La Habana, Cuba), MA in Museology (Universidad Iberoamericana, Mexico). Founder & Editor of WYNWOOD, The Art Magazine. Editor of ARTPULSE and ARTDISTRICTS.

Filed Under: Reviews