« Features

The Unbearable Aura of a Website. Originality in the Digital Age

Eva and Franco Mattes aka 0100101110101101.ORG, Jodi.org copy, 1999, website screenshot. Courtesy of the artists.

With the digital medium, Benjamin’s theory about the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction seems to have reached its dead end. When there is no difference between copy and original, the aura fades and rarity can only be artificially simulated. Yet, is it always true? Playing with Benjamin and Groys, this article shows how, like the mythological Phoenix, aura can resurface in the most replicable digital artifact: the website.

By Domenico Quaranta

COPY AND ORIGINAL

On July 8, 1999, the New York Times published a story reporting on a mysterious European activist group, whose practice consisted in copying art websites and publishing them on the address 0100101110101101.org (Mirapaul). The article described this practice as an “attack on the commercialization of Web Art,” yet it was more than that. With their thefts, 0100101110101101.org wanted to state clearly, on the one side, that the Web was- and should always be- the place of free access to knowledge; and, on the other side, that the digital medium finally turned the word “original” into nonsense.

This is true, of course. Take a given file, copy it, and you’ll have a perfect copy of the “original,” described by the same long string of 0s and 1s. Copy it again, and again, and again, and you’ll get the same. No loss of quality, no material difference between the first file and the last one. Put this file online, and everybody will make a perfect copy of it just viewing it on his browser.

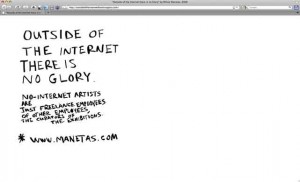

Miltos Manetas, Out Of The Internet There Is No Glory, 2007, website screenshot. Courtesy of the artist.

If the difference between copy and original fades, the concept of the “limited edition” turns into a convention as well. In visual arts, limited editions were introduced with print. Printing techniques such as xylography or lithography used a matrix that deteriorated over time, and the number of good prints that you could get from a single matrix was limited. Modern printing techniques, photography, and video turned the limited edition into a mere convention: an artifice that still made sense someway, related as it was with access to the means of production and to the “source” of a given content- i.e., the negative in photography.

But what does it mean to edition a website, a digital video, or a digital image? If I copy a DVD, I will have a perfect copy of it- no loss of quality, no material difference. If I have access to the same image file and the same printing machine, I can make a perfect copy of a digital print. In the digital realm, rarity doesn’t exist: it can only be artificially simulated.

THE INVISIBLE ORIGINAL

Yet, this is only part of the truth, the macroscopic difference between the digital realm and the material world that made some enthusiasts, at the end of the 20th century, announce the end of intellectual property and of any cultural market. In fact, the digital medium doesn’t destroy concepts such as “original,” “rarity,” and “aura”– it just forces us to reconsider them. In his essay “From Image to Image File - and Back: Art in the Age of Digitalization,” Boris Groys discusses the difference between the digital image and the image file.1 According to Groys, there can’t be a copy without an original. In the digital realm, the original is the image file. Yet, “the image file is not an image - the image file is invisible”: an invisible string of digital code that turns into an image only when “performed” by a machine (84). The digital image is just a copy (a documentation) of an invisible original. In the process of visualization, “the digital original [...] is moved by its visualization from the space of invisibility [...] to the space of visibility [...]. Accordingly, we have here a truly massive loss of aura - because nothing has more aura than the Invisible (86).”

For Groys, visualizing a digital file is a sacrilege. In the computer environment, this loss of aura is permanent, and can be “cured” only by curating: bringing it to the exhibition space, adopting the sacerdotal role of visualizing the Invisible. In other words, the digital image is only apparently ubiquitous and infinitely reproducible in any place: in order to “guarantee its own identity in time,”(84), the digital image has to be located in a specific place (the exhibition space).

THE TOPOLOGICAL AURA

Groys is here relying on Walter Benjamin’s “topological definition of aura,” as he calls it in another essay, discussing how the medium of installation can turn art documentation into art again.2 According to Benjamin, “even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be. [...] The presence of the original is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity.”3 Benjamin calls this presence (better translated as “its here and now”) the aura of a given artwork. So, mechanical reproduction doesn’t destroy the aura, it just depreciates “the quality of its presence,” because “by making many reproductions it substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence. And in permitting the reproduction to meet the beholder or listener in his own particular situation, it reactivates the object reproduced.” This is a crucial point: aura is not lost- we just lose the ability to perceive it because we depreciate the here and now. But aura can be restored, thanks to the increasing importance of what Benjamin calls the “exhibition value” of a work of art; or, in Groys’ words: “(post)modernity enacts a complex play of removing from sites and placing in (new) sites, of deterritorialization and reterritorialization, of removing aura and restoring aura (64).”

Now, let’s go back to the digital file again. According to Groys, the aura of a digital file is the consequence of its own invisibility; any visualization of the invisible original sacrifices its aura to the needs of documentation; and the only way to restore it is to locate the piece in an exhibition. Thus, a digital image is translated into a print, a digital animation into a video installation, a 3D model into a sculpture, etc. Let’s take, for example, Thomas Ruff’s recent series Zycles (2009). The project includes a series of large-format inkjet prints on canvas, displaying abstract images generated by a computer program. The “invisible original” is an algorithm (probably not written by the artist) visualized on a computer by a specific 3D program. The artist takes hi-res screenshots of the computer-generated image and translates them into high quality digital prints released in a limited edition: the photo documentation of a performance (the computer performing the program written by a programmer), turned into “original art pieces” by virtue of the way they are produced and displayed (localized in an art space).

THE UNBEARABLE AURA OF A WEBSITE

Of course, this process is totally legitimate, and it’s, in a way, embedded in our (post)modernity. Yet, we shouldn’t forget that these prints are surrogates. And we should also wonder: is it possible to preserve the initial aura of the digital file or to restore it in a digital environment? Is it possible to create an auratic, digital original? At this point, we may be able to translate this question into another: is there a “here and now” for a digital artifact? Can it be located, and where?

Any file has, of course, a specific location on a computer, described by the file path: Apple/Videos/Cremaster.mov. But this is a private location, it can’t be perceived as an “exhibition space.” It’s just a file on a computer. Now, open a Web address. The same artifact appears in front of your eyes. It’s not a file on a computer: it’s an object you meet during a trip, in a specific place called, let’s say, YouTube, situated in a bigger place called World Wide Web. You can see all this in the location bar of your browser, where the URL of the site is displayed. Now, please read Benjamin’s definition of the aura of a natural object. He writes: “We define the aura of the latter as the unique phenomenon of a distance, however close it may be. If, while resting on a summer afternoon, you follow with your eyes a mountain range on the horizon or a branch which casts its shadow over you, you experience the aura of those mountains, of that branch.”4 Can you find somewhere a better description of Web surfing? Can you find another place that can be, at the same time, so close to the visitor and so far away from her? When you visit a website, it’s simultaneously on your computer and on a server somewhere else in the world. If you are lucky, a bunch of other people is visiting it at the same time: an old German lady, sitting on her sofa; a Japanese secretary in her office; a Swedish teenager in his bedroom. This is the “here and now” of a website: download it onto your desktop and you’ll lose it.

In other words, a Web address gives to any file a presence, an aura. A website- or any file experienced through the Internet- is an auratic, digital original. Technically, a website is a collection of files located on a shared computer space, associated to an Internet Protocol (IP) address (a numerical label assigned to any device participating in a computer network) and to a Uniform Resource Locator (URL). If a website is a building, the IP is its position on the map (i.e. 1071 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10128-0173) and the URL is the name currently used to identify it (i.e., Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum). As a whole, a website can be described as an installation: it locates a series of fragments (documentation of invisible originals) in a specific, unique place. You can go to that place using a browser and clicking on a link. As any real original, if the link is wrong, or the website is not there anymore, you can’t experience it. You may experience an identical copy locally, but it won’t be the same thing: you will miss the aura of the original piece.5

This “aura” is the result of a unique relationship: the one between the content of the website and its location. I’m not the first to say this. One of the first sites cloned by 0100101110101101.org in 1999 was Art.Teleportacia, described by its author, the Russian artist Olia Lialina, as “the first online art gallery.” Opening a Web gallery, Lialina was not contributing to the commodification of the Web, but she was making a statement, at the time provocative, about the unique aura of a website. In a later text, she defines the URL as “the only parameter which protects copyright” (Lialina) of an online work, and makes a series of examples where the location bar becomes an integral part of the work. One of her works is particularly useful to show it. Agatha Appears (1997) is a short metaphorical love story between Agatha, the main character, and the Sysadmin, a term describing a person employed to maintain and operate a computer network. The central part of the story is a “trip through the Internet,” told using the location bar content in a literary way. Agatha and the Sys move from server to server, from country to country, only by means of a click. The work is full of Internet jargon and displays the formalism typical to early net.art, but it’s still one of the best and more enjoyable online works ever made, also thanks to a recent restoration.

Another artist who got the importance of the relationship between the location and the content of a website was Miltos Manetas. In 2000, Manetas launched the Neen movement, a label that gathered a wide number of artists.6 Most of them were working online. As Manetas wrote in a prophetic essay:

Websites are today’s most radical and important art objects. Because the Internet is not just another ‘media,’ as the Old Media insists, but mostly a ‘space,’ similar to the American continent immediately after it was discovered- anything that can be found on the Web has a physical presence. It occupies real estate (Manetas).

A typical Neen artwork can be described as a dedicated Web address displaying a single content: a sound file, an animation, a video, an image, an interactive piece of software, a text. Thus, francescobonami.com is a website displaying a theoretical text about Neen; jacksonpollock.org is an interactive Flash animation allowing you to paint a Jackson Pollock; jesusswimming.com is a silly animation displaying exactly what the URL says; so does jesusdrowning.com, an homage to Manetas by Rafael Rozendaal, one of the best and more prolific authors of Neen websites. Neenstars (as Neen artists call themselves) create “places” for the Internet, where one can stop for a few seconds, take a rest from the information overload, be surprised, and go ahead.

In the following years, many young artists, with little or no connection to the Neen movement, started making “single serving sites”7 like these. Sometimesredsometimesblue.com, for example, is a monochrome website by Damon Zucconi; etherealself.com, by Harm Van Den Dorpel, is a site that captures the video streaming of the user’s camera and displays it on a diamond; and etherealothers.com is a parent website where all the faces of the visitors of etherealself.com are displayed in a grid.

Apart from this, an increasing number of artists, more or less known, have a consistent Web activity. Paul Chan, Ryan Trecartin, and Cory Arcangel are probably the most visible examples. Most of Paul Chan’s publications, animations, fonts, and sound works can be downloaded for free from nationalphilistine.com, his place on the Internet. Trecartin doesn’t even have a website, but he got well-known through YouTube before starting to build a reputation in the contemporary art world. One might wonder which version of I-be Area has more aura: the online, low-res version, visited by up to 50,000 people, or the hi-res, gallery version of the video.

Another legitimate question might be: why didn’t websites become the ultimate collectible? Why do collectors still prefer to buy offline versions of a digital piece released in a limited edition instead of websites? Both these choices require faith: you need faith in the workings of the art world in order to believe that the DVD you bought for 10,000 Euros is more valuable than the online version of the same video. This is a kind of faith a collector can deal with. But what happens when you buy a website? You have to first get used to a different concept of owning. You own something that is - and must be, in order to keep its aura - accessible to everybody; something unique, but whose content can be easily copied by everybody; something living in the public arena, that you can’t protect as if it were in your storage space; something subject to the variations of its own environment and of its visualization software. Furthermore, you need faith because you are buying an invisible original: a bunch of data stored on a server and accessible from a specific online location. In other words, you need the faith required to recognize art out of the context that, along the last century, acquired the ability to turn everything that is shown there into art: the exhibition space.

WORKS CITED

- Groys, Boris. Art Power. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2008.

- Lialina, Olia. “Location = YES.” art.teleportacia, n.d. Oct. 2010. <http://art.teleportacia.org/Location_Yes/index.html>

- Manetas, Miltos. “Websites Are the Art of Our Times.” Manetas.com, 2002 - 2004. Oct. 2010. <http://manetas.com/txt/websitesare.htm>

- Mirapaul, Matthew. “An Attack on the Commercialization of Web Art.” New York Times 8 July 1999: n. pag. Web. Oct. 2010. <http://www.nytimes.com/library/tech/99/07/cyber/artsatlarge/08artsatlarge.html>

NOTES

1. See, Groys, 83 - 91.

2. __________ “Art in the Age of Biopolitics: from Artwork to Art Documentation.” Art Power, Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2008. 53 - 65.

3. Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Trans. A. Blunden. Marxists Internet Archive, Feb. 2005. Oct. 2010. <http://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/benjamin.htm>

4. Benjamin

5. A copy uploaded on another website can, in turn, acquire a new aura by virtue of its relocation. When Slovenian artist Vuk Cosic put on his website a copy of the Documenta X site, declaring it an Internet readymade, he added the aura of art to an object that had, so far, just the aura of the “natural object,” in Benjamin’s terms. We could even develop this further, and say that the Internet is probably the only place where aura is not connected with authenticity. A work by Vuk Cosic has the aura of the original artwork and of the located object; a copy of the same work by 0100101110101101.org has, again, the aura of the located object and of a work of appropriation art.

6. For more about Neen, visit http://www.manetas.com/eo/neen/.

7. The definition was coined by Jason Kottke, who runs the blog kottke.org. <http://kottke.org/08/02/single-serving-sites>